Scientific classification

Kingdom:Animalia

Phylum:Nematoda

Class:Secernentea

Subclass:Diplogasteria

Order:Tylenchida

Superfamily:Tylenchoidea

Family:Heteroderidae

Subfamily:Heteroderinae

Genus:Globodera

Species:G. pallida

Binomial name:Globodera pallida

Introduction

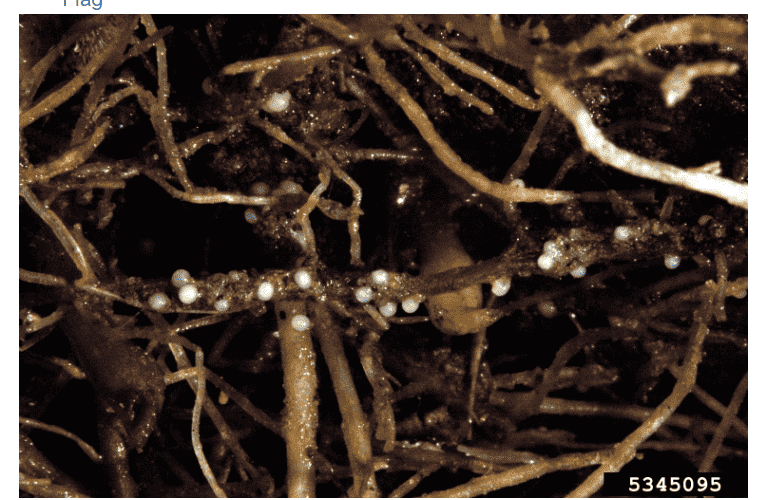

Globodera pallida is a species of nematode in the family Heteroderidae. It is well known as a plant pathogen, especially of potatoes. It is 'one of the most economically important plant parasitic nematodes,' causing major crop losses, and is a model organism used to study the biology of cyst nematodes. Its common names include potato cyst nematode, white potato cyst nematode, pale potato cyst nematode, potato root eelworm, golden nematode, and pale cyst nematode.The female has a globe-shaped body with a thick, lacy cuticle. It retains its eggs inside its body rather than releasing them, and becomes a brown cyst when it dies.The female is white to cream in color. Globodera rostochiensis is similar in appearance, but the female is yellow in color for part of its life.The male has a wormlike body which is held in a C- or S-shape.This nematode is thought to be native to the Andes. Today it is found in 55 countries, mostly in temperate regions. The microscopic cysts are tough and can survive in soil particles, which are transported around the world on objects such as farming equipment and in flowing water. It has been primarily distributed on potatoes, which were introduced from South America to the rest of the world. It can also live on other solanaceous crops such as tomato and eggplant, and many solanaceous weed species, such as black nightshade (Solanum nigrum).The juvenile nematodes feed on the roots of the plant. Eggs develop inside the females after fertilization, and when the females die they become tough cysts that protect the mature eggs. The eggs in the cysts can remain viable for up to 30 years. The cysts detach from the roots and drop into the soil, where they can be distributed via soil movement. An infested plant becomes yellow and wilted and loses its leaves.This nematode is an important agricultural pest, especially in Europe. It causes economic losses of about £50 million per year in the United Kingdom alone. Laws defining best management practices have been passed to reduce the spread of the pest. The movement of soil and potatoes across national boundaries is monitored with quarantines. Farming equipment is cleaned, soil is tested for nematodes, contaminated soil is kept out of fields, and resistant cultivars of crops are alternated with susceptible varieties to reduce the possibility that a more virulent nematode will arise through selection.The nematode is found nearly worldwide today, but it has been mostly kept out of the United States due to rigid quarantines. An exception is one outbreak that occurred in Idaho in 2006. Upon discovery of this outbreak, Japanbanned potato imports from the United States for several years.The genome of this nematode has been sequenced.

Pathology

The golden nematode negatively affects plants of the family Solanaceae by forming cysts on the roots of susceptible species. The cysts, which are composed of dead nematodes, are formed to protect the female's eggs and are typically yellow-brown in color. The first symptoms of infestation are typically poor plant growth, chlorosis, and wilting. Heavy infestations can lead to reduced root systems, water stress, and nutrient deficiencies, while indirect effects of an infestation include premature senescence and increased susceptibility to fungal infections. Symptoms of golden nematode infestation are not unique, and thus identification of the pest is usually performed through testing of soil samples. An infestation may take several years to develop, and can often go unnoticed for between five and seven years. After detection, however, it may take up to thirty years for the pest to be effectively eradicated.

Distribution

The golden nematode, along with the pale cyst nematode, originated in the Andes Mountains of South America. It was first discovered in Germany in 1913, although it is thought to have arrived in Europe with imported potatoes sometime during 19th century. It was first discovered in the United States in 1941, in Canada during the 1960s, in India during 1961 and in Mexico during the 1970s.[1] It has also been found in various locations throughout Asia, Africa, and Australia.

Controversy

Financial compensation was arranged for affected farmers. Nevertheless, for many Saanich farmers the quarantine caused considerable and long-lasting financial damage, particularly for those who had invested heavily in formerly lucrative potato industry. In 1991, farmers announced that alternative crops had not been viable replacements for their former crops. Exacerbated by a poor growing season in which some Peninsula farmers lost approximately 40% of their crops, several farms were going into debt while selling their new vegetable crops at a loss. Several farmers called for a revision or repeal of the quarantine, suggesting that the nematode had been effectively eradicated. Lobby groups throughout BC, however, appealed to the provincial and federal governments to retain the ban, arguing that even the remote possibility of spreading the golden nematode by opening up the Saanich Peninsula to international trade would negatively impact the BC vegetable industry A decision was made to retain the ban, and appeals to the government by Saanich farmers for redress were refused on the grounds of previous financial restitution.

Impact

The golden nematode infestation and the resultant ban on root crop growth, especially potatoes, had both direct and indirect consequences for the Saanich Peninsula community. Foremost, several large-scale farms were forced to sell portions of their land, encouraging a trend away from industrial farming and toward smaller-scale farming on the Peninsula. Additionally, the Peninsula farmers were forced to look to alternate crops and agri-tourism solutions to remain afloat; the Golden Nematode Order banned the growth of potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers, which together account for approximately 50% of all fresh vegetables consumed by Canadians. Without access to this substantial portion of the market, Peninsula farmers sought alternate crops, which included kiwis, berries, and grapes. Thus, combined with outside competition and new industries taking priority, the farming industry has substantially diminished on the Saanich Peninsula. It has been suggested that while fifty years ago, over 90% of food on the Peninsula was grown locally, by 2004 this percentage had dropped below 10%.